Welcome to Hemlock and Canadice Lakes!

Barns Businesses Cemeteries Churches Clinton & Sullivan Columns Communities Documents Events Time Line Fairs & Festivals Farm & Garden Hiking Homesteads Lake Cottages Lake Scenes Landscapes Library News Articles Old Maps Old Roads & Bridges Organizations People Photo Gallery Podcasts Railroad Reservoir Schools State Forest Veterans Videos

|

The Marcus Hoppough Homestead at 4593 N. Main St. Hemlock NY |

Click any image to enlarge. |

|

The Miller’s House - The Marcus Hoppough House at 4593 Main Street

A Historical review by Joy Lewis, the Richmond NY Historian.

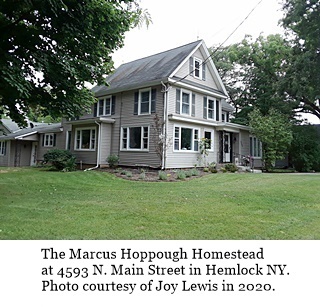

1 The Marcus Hoppough Homestead at 4593 N. Main Street in Hemlock NY. Photo courtesy of Joy Lewis in 2020. The House is Built: 1853 The Marquis de Lafayette was a French nobleman and military officer impassioned by the American colonies’ bid for independence. At his own expense he commissioned a sailing vessel, the Victoire, and arrived in South Carolina in June of 1777 with the intention of offering his services to the American forces. Within two months he’d met and been befriended by General George Washington, was made a Major General in the Continental Army, and participated in a significant battle. For the next two years he adeptly commanded troops on the fields of battle at Brandywine in Pennsylvania and Monmouth in New Jersey. He returned to France for a year’s respite, but was back in Virginia early in 1781. In October he engaged the enemy in a pincer movement in concert with Washington that culminated in the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown. In consequence, Lafayette was a much-admired national hero. Hundreds of American boys were named in his honor in the three decades following the Revolutionary War. Many were called “Lafayette,” some were named “Fayette,” and others “Marquis” — pronounced “Marcus” and sometimes spelled that way. At least one little boy, born in the summer of 1807 in central New Jersey, was given the full treatment: “Marquis de Lafayette,” the second-born son of Peter and Margery Hoppough. The child was called Marcus. In his early twenties Marcus, his parents, and ten siblings came from New Jersey to settle in Canadice, New York. A year after their arrival the youngest Hoppough sibling, Minerva, was born. Peter Hoppough owned a farm and a sawmill and his boys worked alongside him until, one by one, they married and struck off on their own. Marcus was in his early forties when he married Betsey and settled on a farm near his parents in Canadice. Their daughter Mary was born in 1851. She was nearly two years old when Marcus and Betsey made the move to Hemlock. Hundreds of acres and half-a-dozen properties, costing upwards of $10,000, were bought by Marcus, including farm land along the Hemlock Outlet and Clay Street, as well as several properties and lots on Main Street. This lot (4593) is where he chose to build his home. Mr. Hoppough bought the sawmill and the grist mill on the outlet creek on the west side of Main Street and he bought more than two hundred acres of land to the west and south of the mills. When he built a dam at the mill site, this land was flooded to create a mill pond — known as Hoppough’s Pond long years after Marcus had passed away. The year after moving into their new home, in 1854, Betsey Hoppough gave birth to her second daughter, Fannie. Mary was ten and Fannie seven when their baby brother Horace was born on October 26, 1861. Two years later a measles epidemic swept through the village. Mary Hoppough died on October 8, 1863 and Fannie a week later. Two-year-old Horace was spared, yet his life was blighted as he never recovered his wits; he died at age thirty-one in a Canandaigua asylum. When the sawmill and the grist mill came into his possession, Marcus invested heavily in their refurbishment. The sawmill was updated with a turbine wheel, which greatly increased its efficiency. The old grist mill, with its ancient water wheel and three run of stones, was torn down in 1856 and completely rebuilt, modernized with an overshot wheel, new wooden shafts, and four run of burr stones imported from France. During the twelve years he’d been living in Hemlock, Marcus continued to invest in property — buying a lot here, selling another there; there are scores of his property transactions recorded in the Livingston County Clerk’s office. In 1865 he bought the lot on the north side of his home — the old cooper shop. He built a small house on this lot (4581), which was used for decades as rental property. Five years later Marcus sold the entirety of his Hemlock properties: the mills and mill pond, both houses, and the farm land. He stayed on to operate the mills for another three years, then retired to live out his days at Livonia Station. He died there in March 1889, a month before the death of his son Horace. The Marcus Hoppough family — husband, wife, two daughters and a son — all lie in adjoining plots in Livonia’s Union Cemetery. The Miller’s House: 1870 William R. Utley of Brooklyn purchased the Hoppough Mill Properties on behalf of the Rochester Waterworks Company. He did not live in Hemlock, but engaged a manager to oversee the businesses. After Marcus Hoppough retired, the manager for a good many years was Samuel Northrup, an eminent local lawyer. In 1876 Mr. Northrup hired John Haskell Gilbert to operate the mills and installed him in the miller’s house. It had been more than two decades since Haskell and his wife Lucia had lived in Hemlock. Years earlier they had lived in the house next door to the south (4599) when he ran the mills which belonged at that time to Samuel Pitts. In the years since 1853, after leaving Hemlock, they’d lived in Livonia Center, Mendon, and Richmond; at each place Haskell was manager of a flour mill. Now he’d been installed by Mr. Northrup to oversee the work at the sawmill and the flour mill on the Hemlock Outlet. The Gilbert family had grown to include three daughters: Rose was seventeen; Lillian, fourteen, and Isabelle, ten. Their firstborn, Randall, had died at age seven, shortly before Lillie was born. The Gilbert family lived in Hemlock for about ten years; they were living in Richmond Mills when Lucia died in the spring of 1884. The Woodruff Family - Father: 1886 Buel D. Woodruff of Livonia bought the mill properties in Hemlock — a sawmill and a grist mill, the mill pond (all its water and all the land under the water), hundreds of acres of farm land, and two houses on Hemlock’s Main Street. Born in July 1830, Buel was the son of Austin Woodruff and Julia Smith. In the winter of 1792 Austin was a five-year-old child when he came from Connecticut with his parents, Solomon and Susannah, and a younger brother to settle on what would, in later years, become Federal Road south of Livonia Center. (There is a historical marker on Federal Road marking the spot.) A year earlier Solomon Woodruff had journeyed alone to the Genesee Country where he paid eighty dollars for one hundred sixty acres of virgin land. He put up a log cabin, then returned to Connecticut to fetch wife and sons. A 1925 article in the Livonia Gazette recounted the hazards faced by the Woodruff family as they traveled to their new home: “In February [of 1792 Solomon returned to New York] this time with wife and two small sons and a few household goods upon a rude sled drawn by two 2-year- old steers. After twenty-six days of travel through snow and in bitter winter weather, the younger boy sickened and died. The father dug a shallow grave, and there by the roadside on a bleak Bristol hill they buried the child. Coming on to the clearing in the wood, they found that the Indians had burned the cabin, and that they were homeless in the forest. Retracing their way to the home of Peter Pitts at the foot of Honeoye lake, Mrs. Woodruff and son found shelter until a new cabin could be erected.” Austin, the little boy who’d endured with his parents the arduous winter trek from Connecticut, married, settled in Livonia township, and for a single term (1849) served as Town Supervisor. He and his wife Julia had thirteen children, of whom Buel was the tenth. In 1855 Buel married Hortensia Harding; they lived in Hornellsville (now Hornell, Steuben County) until after the birth of their second son Edward. In 1859 they came to live in Livonia, settling near family. Their elder boy, Herbert, was three and Ed an infant. Frankie was born two years later, but drowned before his third birthday. The youngest Woodruff boy was another Francis, born in 1865. Buel’s wife died just a few years later and he remarried, though he had no more children. For more than thirty years Buel had lived in Livonia when in 1881 he was elected as Town Supervisor; he served two terms. Four years later, when the mill properties in Hemlock were offered for sale, Buel Woodruff, now in his late fifties, was the successful bidder. He did not, however, live in Hemlock, nor did he manage the properties. It was his son Edward who lived in the mill house and who managed the grist mill, converting it to a roller mill early in his tenure. The sawmill, in sad repair, was decommissioned. The two-hundred-acre mill pond was rechristened the “Woodruff Pond.” On November 12, 1890, downtown Hemlock suffered a devastating fire. The Livonia Gazette noted that the fire was the worst Hemlock had experienced in over twenty years. “The fire was first seen about half-past 4 in the morning by Eri Jenks and Frank Blackmer, who had started out after duck. It was in the southwest corner of the store occupied by J. B. Patterson, and away from the main room. They gave the alarm and a number were on the ground in a few minutes, and as the church bell was rung and a general alarm sounded, every man and woman in the village was on the street. It was impossible to put out the fire ... It spread very rapidly.” On the west side of Main Street was a large building owned by Robert Hoar. Housed in the downstairs of the building was the clothing store of Mr. Patterson and the Post Office. Dr. Frederick A. Wicker, Postmaster, had his medical practice on the upper floor. The building was a total loss, though much of the Post Office paraphernalia was able to be saved, including the mail boxes and all the stamps and post cards. Mr. Patterson watched helplessly as most of his stock of ready-made clothing went up in flames. Of nearly a thousand dollars’ worth of merchandise less than a tenth was saved. Insurance, it was reported, would not cover his losses. To the north of the Patterson Store, bordering the creek, was the Heath Dry Goods Store. Mr. Heath and his family lived upstairs. With great effort this building was saved. Not so the Williams Building on the south side of Patterson’s, in which James Morton operated a General Store. The news story is detailed: “It was seen soon after the fire got well under way that there was no chance of saving Morton’s store, and the people of the village who were not doing good service in other directions were removing show-cases and goods to the building across the street.” Nonetheless Morton’s loss was heavy. In part of the Williams Building was located the shoe shop of James Kinney and upstairs was a room, in which the entire household goods of Mrs. Emily Stacy were stored. Nothing but ashes remained of either enterprise; neither Mr. Kinney nor Mrs. Stacy had insurance. Although it did not burn, the office of Justice Charles E. Owen on the south side of the Williams Building was also lost, for it was torn down in order to save the home of Mrs. Sarah White. The White house took fire several times during the morning, but was saved by the heroic efforts of the crowd. Nearly an entire block of downtown lay wasted, from the creek to Water Street. Only the Heath Store on the north end and the White house on the south end remained; all in between was devastation. Over the next few years the mess was cleared away, insurance claims were settled, empty lots were sold, and new buildings arose. It was Buel Woodruff’s son Edward who bought up much of the vacant property and who, in partnership with John P. Coykendall, rebuilt the shops and stores. And thus, in 1898, was erected the “Woodruff Block.” The Woodruff Family - Son: 1907 An interesting, creative man was Edward Woodruff, second-born son of Buel and Hortensia. At age twenty-one he married Georgiana Quackenbush; she gave birth to two children: Emma and George before she died in 1882. A few years later, when his father bought the Hemlock mill properties, Edward took over as manager. One of his first acts was to convert the grist mill to a roller mill and to pull down the old sawmill. He and his children settled in to the miller’s house on Main Street. In the autumn of 1891 he married again, to Flora Naracong. He bought his bride a new piano and had it installed in the front room. In the third year of their marriage Flora gave birth to a daughter on Independence Day, but did not survive the process. Her daughter Berta was two when Edward married again in the summer of 1896. His third wife was Isabelle Gilbert, youngest daughter of John Haskell Gilbert. As a girl she’d lived in this house during the years her father had been manager of the mill. Her two daughters were born in Hemlock: Marian in 1898 and Doris three years later. Very active in town and village life, Mr. Woodruff served as Livonia Town Justice in 1899. He managed his father’s mills with efficiency and oversaw the construction and the leasing of the Woodruff Block. This was a sizeable, two-story building of seven bays, accommodating Mr. Humphrey’s Meat Market, the department store of George Knapp, a barber shop and pool room, and the lodge rooms of the Odd Fellows and Maccabees. Built in 1898 it replaced the buildings lost by fire a decade earlier. E. B. Woodruff was involved with several businesses in Livonia, including the banking firm of Woodruff and Thurston (founded 1902) and Woodruff, Reed, & Company — “dealers in fertilizers, Plaster, Lime, and Cement.” He bought houses in Hemlock and Canadice, which were let as income property. In addition to his other enterprises, he operated for some years as a “dealer in fine carriages and farm wagons.” In 1903 Edward Woodruff was elected Livonia Town Supervisor, serving with distinction as had his father and grandfather before him. He was appointed Hemlock Postmaster early in 1907. In that year he bought from his father the mill properties, including all the lands and dwellings that had been associated with the mills since Marcus Hoppough’s original acquisition half-a-century earlier. His Hemlock Lake Roller Mill expanded to produce several varieties of fine flours: Pride of Hemlock, Fancy Baker’s Flour, Gilt Edge, and Golden Crown. Less than a year later, in February 1908, the Woodruff Block was destroyed by fire. A report of the fire appeared in the February 7 edition of the Livonia Gazette: “The building known as the Woodruff block, on the west side of Main Street, was entirely destroyed last Saturday night by one of the worst fires in the history of the place. The flames were noticed first in the rear room of Humphrey’s meat market, and were discovered about half-past 10 by Frank Bromley, who lost no time in giving the alarm. A blizzard was raging, and with the high wind the flames soon spread throughout the structure and the whole building was soon a mass of flames.” The heat was so intense and the wind so strong that for a time the buildings across the street were in danger of catching fire. Wet blankets were hung over windows — some cracking from the heat — and snow and water were flung about by energetic fire fighters. “By half-past twelve,” the Gazette reporter noted, “the building was in ruins.” Mr. Woodruff reported that the Post Office was nearly a total loss. About the only thing to be rescued was the safe, which held the account book and all the stamps. Within days of the fire the Post Office was up and running, for “the old post office which [had] been stored away in William McLeod’s barn, [was] brought into commission again, and placed temporarily in a room in D. J. Kavanaugh’s house.” It was not long after the fire that Edward and Isabelle retired to live with a daughter in Rochester. The House is Sold Again: 1924 The Woodruff family moved away from Hemlock around 1908, but they did not sell their home. For some years the house was rented. In 1910 Amos Swan and his wife Alice, both in their early thirties, lived here with two boarders: Oscar Lee, in his fifties, worked at the former Woodruff flour mill (owned at this time by Edward Dwyer); and Lida Francisco, sixteen, was the Swans’ housekeeper. In 1915 Ellsworth Cole, a farmer in his middle years, rented the house; he lived here with his wife Altie. By 1920 the house was standing empty; three years later Edward Woodruff died. Late in 1924 Isabelle sold the house to Orville and Ellen Childs. Orville was a farm worker, finding work on area farms from day to day. The elderly couple’s two surviving daughters, Grace and Flora, were both married. Grace, who lived on Adams Road, was the wife of Byron Carpenter and the mother of two children. Flora lived in New Jersey, her husband Fred Metzger’s native state; they had two sons. For more than a decade the Childs family had lived in Hemlock, moving house every few years. When they bought this property, they stayed less than four years before going to New Jersey to live with daughter Flora’s family. It was in New Jersey that Mr. Childs died. The Livonia Gazette reported the details on May 29, 1936: “The community was shocked to hear of the death of Orville Childs on Monday evening. Mr. Childs had been in ill health for a long time and it is believed that was the reason for his becoming despondent and taking his life. He was 75 years of age and is survived by his wife, Ellen; two daughters, Mrs. Grace Carpenter of Hemlock and Mrs. Flora Metzger of Newark, N. J.; four grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. Funeral services were held from his late home Wednesday at 2 p.m. with interment in Union cemetery, Livonia.” The Doctor’s House: 1928 Dr. Harold Trott bought the house in August 1928. He was twenty-nine years old, and married to Hazel, a pretty young woman he’d met during his college years. From Ontario, Canada, Dr. Trott had discovered the “charming” village of Hemlock a few years earlier, when he was working at the Lee Hospital in Rochester. A co-worker invited him to spend a week’s vacation at Hemlock Lake and the doctor became enamored of the picturesque scenery, the friendly townsfolk, and the healthy, invigorating air. While at McGill College in 1919, where he was enrolled in the medical studies program, Harold suffered for a year with Landry’s Paralysis (today known as Guillain-Barré Syndrome), an inflammation of the peripheral nerves. For eleven months he lay upon his bed, almost completely paralyzed. Even his breathing was compromised, but through the faithful ministrations of his doctors, gradually he improved. He was the first patient up until that time to survive this debilitating disease. With effort he did eventually recover the use of his legs, though he had to wear braces for the rest of his life. After missing one full year of his studies, he enrolled at the University of Western Ontario, where he completed two years. Then it was back to McGill for two more years, graduating in the spring of 1924. Some months later he was married and within the year was set up in practice in Hemlock. He and Hazel rented a house on Main Street before buying the mill house in 1928. For several years Dr. Fred Kenzie, Dr. Trott’s assistant, lived and worked with him. Harold Trott was a man of many interests. The same year he bought his new home, he bought an airplane, learned to fly, and created the Hemlock Airport north of the village on Route 15A. Jack Evans, Dr. Trott’s teen-aged neighbor, wrote in later years “Hemlock Memories,” in which he recalled Dr. Trott’s love of flying: My earliest recollection of airplanes came about because our next-door neighbor, Dr. Trott, possessed a fervent interest in the introduction of the private airplane. Dr. Trott probably purchased his first plane around 1925. He fashioned a small airfield north of the village on the high ground between two valleys. It took a stretch of the imagination to have called this field an airport. It was definitely a field, a hay field, with nothing obvious that marked a landing strip. In one corner of this forty-acre field, Dr. Trott erected a small wooden, white painted structure for a hangar. The building had three or four barn doors that could be rolled to one side to permit a small plane ... to enter or exit. Atop the roof of the small hangar was a vertical staff supporting the familiar windsock. Throughout the 1930s “Air Shows” were held most summer Sundays, where aviators gathered “to show off their planes, take up passengers, demonstrate parachute jumps, perform aerial aerobatics, drop small bags of flour at ground targets from low altitudes and other stunts. Dr. Trott’s airfield was one of the meccas of these early airplane enthusiasts.” The festivities commenced in mid-morning and lasted into the early evening. A refreshment stand served hotdogs and soft drinks to the milling crowd. The highway was jammed with cars parked on both sides of the road and a deputy was delegated to control traffic. Such Air Shows were common all around the state and Dr. Trott and his wife traveled far and wide to attend different events. In August 1928 he was on hand at the opening dedication for the small airport at Canastota, New York, east of Syracuse. As was his custom he filmed the activities, which included that day about thirty seconds’ worth of film of Miss Amelia Earhart. Harold and Hazel’s only child, Edward, was born in 1937. It was about that time that the doctor gave up general medicine and for the next twenty years specialized in dermatology at a practice in Rochester. He kept an office at his home still, and was ready to patch up any youngster who needed bandaging. Beverly (Benham) Hoppough remembered a day in the late forties, she was eight or nine, when she fell off her bike right in front of Dr. Trott’s house. Her knee was laid open and bleeding. He kindly ushered her into the office — a room on the north side of the house — cleaned her up, and taped a gauze pad over her wound. He told Bev that day that his home had been enlarged years earlier by tacking a couple of lakeside cottages on to either end. During WWII Dr. Trott joined the war effort, stationed at the veterans facility in Batavia, a Captain in the U.S. Medical Corps. He was then in his early forties, a ruddy-faced man, rather stout, with a trim black mustache and twinkling blue eyes. He had “a flair for conversation” one associate remembered. He wrote three books, all produced during the war years: Santa in Santa Claus Land (1942) was written especially for Iva Outhouse, a young Bristol girl crippled by polio who’d been his patient; Campus Shadows (1944) was his interesting and detailed memoir; and School Memories (1945), was an illustrated scrapbook for collecting a child’s school mementos. In June of 1946, his interest in aviation unabated, he launched publication of “Helicopter Digest,” a 64-page magazine, with himself as editor. Dr. Trott retired in the late fifties, and died May 17, 1961; Mrs. Trott lived another quarter century. Both are buried in Ontario, Canada.

|

||