Welcome to Hemlock and Canadice Lakes!

Barns Businesses Cemeteries Churches Clinton & Sullivan Columns Communities Documents Events Time Line Fairs & Festivals Farm & Garden Hiking Homesteads Lake Cottages Lake Scenes Landscapes Library News Articles Old Maps Old Roads & Bridges Organizations People Photo Gallery Podcasts Railroad Reservoir Schools State Forest Veterans Videos

|

“Nature in the Little Finger Lakes” by Angela Cannon Crothers |

|

|

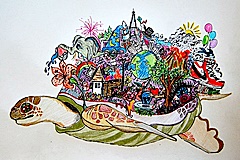

On Turtle’s Back By Angela Cannon Crothers May 2016 While Skywoman was falling to Earth, the animals gathered. They were concerned about making a place for her to land upon. Turtle rose to the surface of the waters. The animals knew something else was needed on Turtle’s back to sustain life for Skywoman—soil. The soil, found at the bottom of the sea and set on Turtle’s back, covered the shell like a great tide giving life to Earth so that the seeds in Skywoman’s hands, and eventually all of humankind, could live upon it. The Iroquois Creation Myth presents the importance of soil. Other cultures from around the globe have creation stories that involve a god who forms humans from clay and dirt, and then breathes life into them. Soil holds the breath of life. The soil at my home, according to the U.S. Geological Survey’s Web Soil Survey, is Vanessa Silt Loam. It’s a sexy name. Loam is a perfect blend of the mineral separates of sand, silt, and clay that make up all soils on Earth. These three ingredients are derived from parent rock material that has been breaking down for hundreds of millions of years. And although I know that anything labeled “loam” is desirable for gardening, when I feel the soil, and squeeze a ball of it in my hand, I can sense there is more clay than silt by the way it holds its shape and sticks to my fingers, rather than feeling slippery like silt or grainy like sand. Clayish soils hold a lot of water, requiring peat moss or organic material to help keep it from sticking together into clods. Soil clods create a condition that removes valuable air space and micropores required for the most important part of soil—all the living things that reside within. Soil is more than a living ecosystem; it’s a world all its own. A single spoonful of soil may contain a billion bacteria, a million fungi, and ten thousand amoebae. On a microscopic level what you see are: bear-shaped, six-legged tardigrades cantering through water droplets filled with single celled amoeba and bacteria, tiny nematodes (nearly microscopic and worm-like) flapping about in a larger stew of giant earthworms, centipedes, terrestrial crustaceans (more commonly known as sow bugs), psuedoscorpions, and mold mites, roaming through mini landscapes of boulder sized sand, silt, and smaller clay particles, all surrounded by a complex network of fungi mycelium that bridge communications between the rhizospheres of grass, herb, and tree roots extending into the dark underground. It’s a lot of wildlife to think about. This living system helps soil provides all of the nutrients, released by microorganisms as well as mosses and lichens, that not only plants need to grow healthy, but that upper world animals, like ourselves, require in order to also be well and strong. Where does the calcium from milk come from? It comes from the soil. How does iron, potassium, and vitamins get into our food? Via the soil. It is said that the authentic taste, or terroir, of fine wine, cheese, and other foods, is directly related to the soil from whence it came. Soil does more than provide essential nutrients and the green beauty of the world, soil also sequesters carbon—a greenhouse gas. Depending on the type of soil, the organic content, weather, and health of the soil, a good, earthy dark, dynamic and decomposing soil can hold billions of tons of CO2. Soil can help with our issues of climate change. The fragrance of soil holds the dreams of the past lives of wild strawberry flowers, the rot of deer scat and its celebratory fungi, dung beetles and worms, as well as the essence of last summer’s brilliant sunshine and the spirit of the swallows chittering and swooping over the tall grasses for flies and gnats. Soil is also joy. I know this because when I am with children in wooded wetlands or digging in a tilled garden, they play in it, laugh in it, and cover themselves bodily in it! Being barefoot on the ground, in the dirt, turns out to be good for our spirits and minds. And how could it not be? The joy of soil brings sweet blossoms and bitter greens, shady trees to rest beneath, and a creative source for building vessels of all kinds. The soil placed upon Turtle’s back was a gift not just for life, but full of its own life as well.

|

||

|

Editor’s Note: Angela Cannon Crothers is a naturalist and writer who teaches at Finger Lakes Community College and with The Finger Lakes Museum. Here are some columns that she has written about the Little Finger Lakes. Her columns also appear in the Lake Country Weekender newspaper.

|

||